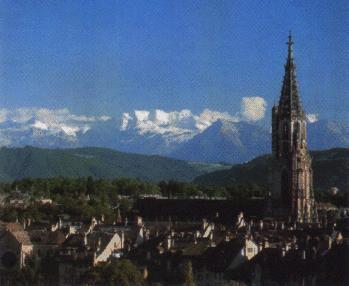

Munster and Alps, Bern

Munster and Alps, Bern

Munster and Alps, Bern

Emanating from a cathedral in the center of Rome, a line of ten thousand people stretches radially outward, like the hand of a giant clock, out to the edge of the city, and beyond. Yet these patient pilgrims are directed inward, not out. They are waiting their turn to enter the Temple of Time. They are waiting to bow to the Great Clock. They have traveled long distances, even from other countries, to visit this shrine. Now they stand quietly as the line creeps forward through immaculate streets. Some read from their prayer books. Some hold children. Some eat figs or drink water. And as they wait, they seem oblivious to the passage of time. They do not glance at their watches, for they do not own watches. They do not listen for chimes from a clock tower, for clock towers do not exist. Watches and clocks are forbidden, except for the Great Clock in the Temple of Time.

Inside the temple, twelve pilgrims stand in a circle around the Great Clock, one pilgrim for each hour mark on the huge configuration of metal and glass. Inside their circle, a massive bronze pendulum swings from a height of twelve meters, glints in the candlelight. The pilgrims chant with each period of the pendulum, chant with each measured increment of time. The pilgrims chant with each minute subtracted from their lives. This is their sacrifice.

After an hour by the Great Clock, the pilgrims depart and another twelve file through the tall portals. This procession continued for centuries.

Long ago, before the Great Clock, time was measured by changes in heavenly bodies: the slow sweep of stars across the night sky, the arc of the sun and variation in light, the waxing and waning of the moon, tides, seasons. Time was measured also by heartbeats, the rhythms of drowsiness and sleep, the recurrence of hunger, the menstrual cycles of women, the duration of loneliness. Then, in a small town in Italy, the first mechanical clock was built. People were spellbound. Later they were horrified. Here was a human invention that quantified the passage of time, that laid ruler and compass to the span of desire, that measured out exactly the moments of a life. It was magical, it was unbearable, it was outside natural law. Yet the clock could not be ignored. It would have to be worshipped. The inventor was persuaded to build the Great Clock. Afterwards, he was killed and all other clocks were destroyed. Then the pilgrimages began.

In some ways, life goes on the same as before the Great Clock. The streets and alleyways of towns sparkle with the laughter of children. Families gather in good times to eat smoked beef and drink beer. Boys and girls glance shyly at each other across the atrium of an arcade. Painters adorn houses and buildings with their paintings. Philosophers contemplate. But every breath, every crossing of legs, every romantic desire has a slight gnarliness that gets caught in the mind. Every action, no matter how little, is no longer free. For all people know that in a certain cathedral in the center of Rome swings a massive bronze pendulum exquisitely connected to ratchets and gears, swings a massive bronze pendulum that measures out their lives. And each person knows that at some time he must confront the loose intervals of his life, must pay homage to the Great Clock. Each man and woman must journey to the Temple of Time.

Thus, on any day, at any hour of any day, a line of ten thousand stretches radially outward from the center of Rome, a line of pilgrims waiting to bow to the Great Clock. They stand quietly, reading prayer books, holding their children. They stand quietly, but secretly they seethe with their anger. For they must watch measured that which should not be measured. They must watch the precise passage of minutes and decades. They have been trapped by their own inventiveness and audacity. And they must pay with their lives.

Einstein's Dreams, Alan Lightman

http://www.moonchild.ch/Philosophy/time3.html